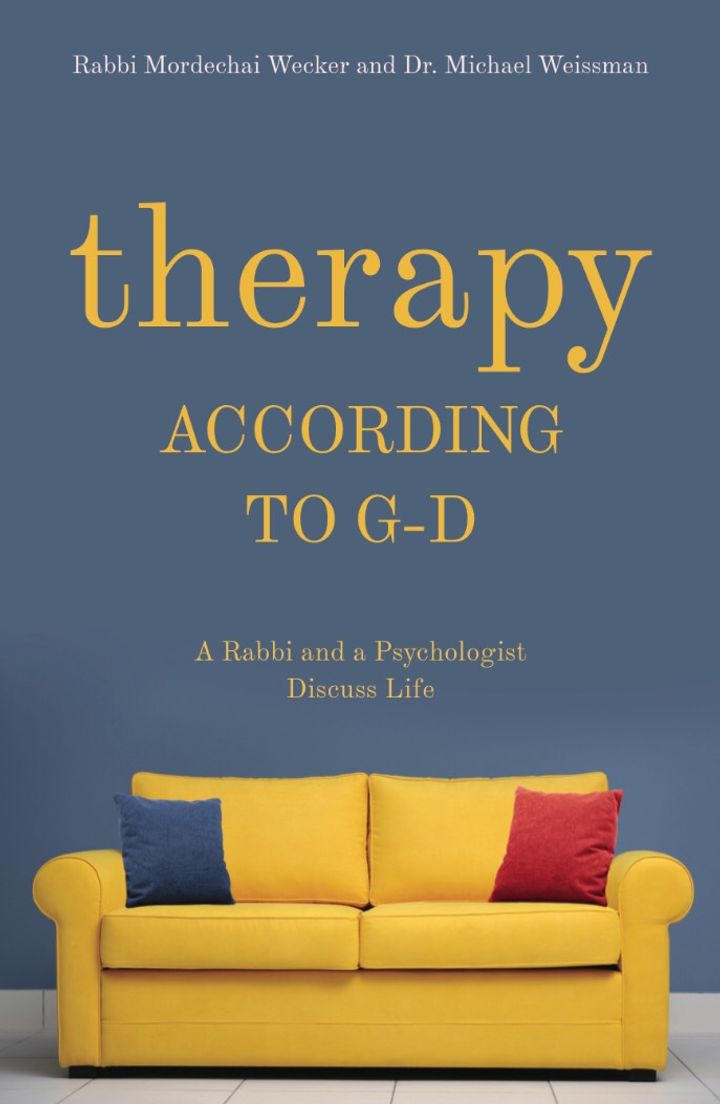

Baltimore, MD - Mar. 5, 2019 - Living a Torah-filled life and working with trained professionals to cope with difficult issues which may arise—including anger, anxiety, family conflict, loneliness, and substance abuse—needn’t be thought of as mutually exclusive. Eternal halakhic principles can provide healing and other benefits when incorporated into daily life. That’s according to a new book (Mosaica Press) co-authored by Baltimore resident and Silver Spring native Rabbi Mordechai Wecker and Dr. Michael Weissman, a clinical psychologist based in Virginia.

The universal Torah principles in which Dr. Weissman grounds his practice may not be explicit to his patients, although the latter do know that the psychotherapist, who wears a yarmulke to work, is an orthodox Jew.

The book is organized around chapters that are based upon mental health challenges. “Our Marriage is Falling Apart,” reads one chapter title, with subsections “Please fix him” and “Please fix her”; another chapter is titled “I don’t know why I’m so depressed.”

The authors decided to pen the book after striking a friendship during the three years that Rabbi Wecker, then head of school at Hebrew Academy of Tidewater, lived in Norfolk, Va. The psychotherapist attended a Shabbos morning class on the parsha that the rabbi taught, and the two soon realized that there were overlaps between their areas of interest and chosen careers. The book combines Dr. Weissman’s 40 years of clinical practice with the four decades of Jewish education experiences of Wecker, who earned his smicha from Rav Moshe Feinstein, Z'TL.

In the class, and socially around each other’s Shabbos tables, the co-authors and friends hammered out first their thesis, and then its many applications and dimensions. They elected, in line with clinical practice ethics, not to name any of the psychotherapist’s patients, but all of the references in the book to anonymized patients are true.

In the “I Don’t Know Why I’m So Depressed” section, for example, the authors tackle a mental disorder that plagues more than six percent of Americans, or 16.2 million adults, according to the National Institutes of Mental Health. Dr. Weissman writes about “John,” a 68-year-old who came to him due to problems in his marriage, although he soon discovered underlying issues of depression and insecurity.

That depression and insecurity, as well as a sense of guilt, reminds Rabbi Wecker of a particular comment of Sforno. At a certain point, according to Sforno, the Jews who recognized their faults nevertheless don’t repent, because they feel that it is already hopeless, given that Hashem has forsaken them.

“There is no point is continuing the teshuvah process, they rationalized, since all is lost. They were overcome with a sense of depression as a result of their perceived inability to rectify their relationship with Hashem,” Rabbi Wecker writes. “This in turn led them to a feeling of despair. This was their mistake.” At their core, then, depression and despair can be manifestations of a lack of faith and trust in Hashem.

The conversation in this, and other chapters, unfolds further. What is afforded the reader, then, is nothing short of getting to be a fly on the wall, or even a student, listening in on an extensive yet accessible chavrusa between a mental health professional and a rabbi.

For further information, please contact Rabbi Wecker at mowecker@outlook.com