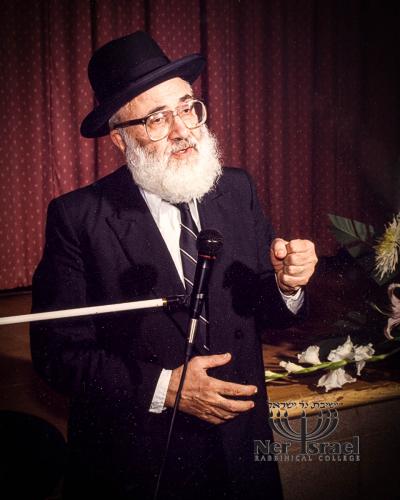

In Memory of Rav Shmuel Yaakov Weinberg, zt'l, written on the Occasion of His Fifth Yahrzeit:

From a Mechutan's Perspective

by Rabbi Emanuel Feldman

I first met Rav Yaakov Weinberg long before he was the famous Rav Yaakov. I was a boy of 15, and he was a few years older. I had come from Baltimore to Mesivta Rabbi Chaim Berlin in New York for a year of high school, and Rav Hutner, the Rosh Hayeshiva, had assigned the young Yaakov Weinberg to be my mentor for a short while. Neither of us had any idea, of course, that many years later, he would become the husband of Chana Ruderman and ultimately the Rosh Hayeshiva of Ner Israel in Baltimore, and that I would become rabbi in Atlanta. And of course, the thought that some day our children would be married to one another, and that we would become mechutanim, could not have entered our minds.

It is from the perspective of a mechutan that I write these lines in his memory.

Who was Rav Yaakov Weinberg? That is not a question easily addressed, for his was a complex and variegated persona. What the world saw was a tall, handsome, articulate Rosh Yeshiva, pious and scholarly, possessed of an incisive mind, a mastery of the Written and Oral Torah, and a unique ability to inspire and uplift his disciples.

He was all these, but he was much more. This prodigious intellect, who was a ease in the company of the great minds of his generation, was also at ease in the company of little children. He was able to switch gears from the most complex and subtle Talmudic discussions to the telling of stories to his grandchildren – and to excel both in the role of world class Torah teacher and world class zeide. He had the rare ability to get down on the floor with his grandchildren, putting his mellifluous voice to good use as he dramatized the bedtime stories – and doing it all in a totally unselfconscious way. When he was with the children, he was not playing the role of I-am-the-famous-rosh-yeshiva-now-playing-with-his-grandchildren; rather, he was being himself – natural and unpretentious. When he played games with them, he was not playing games about himself; he was simply being himself.

This is what I most cherish about him: his unpretentiousness, his refusal to pose. Here was a man who was genuine and unadorned. His distinctive feature was honesty – with others and, even more difficult – with himself. Gaavah, conceit, ego, flatter, and artificiality were not part of his lexicon. His ability to play with his grandchildren was not just a charming trait; it was a manifestation of a personality that had no admixture of self-importance or artificiality.

This genuineness suffused everything he did. Just as his self disappeared when he was teaching a complicated gemara, so did his self disappear when he spoke with the numerous individuals who came to him for advice and counsel about their personal problems. His was a life in search of the emes – the truth – that lay imbedded in the text, whether that text was part of the Torah or part of the people – young and old – with whom he had contact.

He was gentle and sympathetic by nature, but he was intolerant of shoddy thinking. He was an understanding and kind human being, but his was a lifelong struggle against intellectual laziness and religious shallowness. Emes was the key to his life.

Little children know emes instinctively. It is only later, as they mature, that their instinctive emes becomes diluted. When I would see the joy in Rav Yaakov’s eyes as he played with his grandchildren, it occurred to me that perhaps what most invigorated him about them was their instinctive emes, their lack of guile and cunning, their transparency and straightforwardness. He identified with these qualities, because they were a reflection on his own essential being

Yehei zichro baruch.

Rebbe's Awe-Inspiring Legacy

by Rabbi Moshe Hauer

“What is the way that will lead to the love and the fear of G-d?When a person contemplates His great and wondrous works and creatures and from them obtains a glimpse of His incomparable and infinite wisdom, he will straightway love, praise and glorify Him, and long with an intense longing to know His great Name…. And when he ponders these matters, he will recoil frightened, realizing that he is a small creature, lowly and obscure, endowed with slight intelligence, standing in the presence of Him who is perfect in knowledge.” (Rambam: Foundational Principles of Torah, 2:2)

This passage in the Rambam expresses the essential tension within our service of G-d. On the one hand, our awareness of G-d draws us passionately towards Him, as we seek to absorb whatever we can of His wisdom, and to deepen our connection to him through better understanding of the brilliance of His Torah. Yet simultaneously, we struggle with the overwhelming sense of fear and humility created by our deepened awareness of His magnificent presence. On the one hand we are drawn towards Him; on the other we recoil and stand back.

It is this tension that characterized my Rebbe, Harav Yaakov Weinberg, zt”l. Rebbe was absolutely brilliant and incredibly wise, and did not allow a learning session to pass without uncovering broad and deep Torah insights. His incredible passion for learning and thirst for knowledge were a living example of that “intense longing to know [G-d’s] great Name.” Yet even more profoundly and strikingly, Rebbe’s every step and thought were saturated with an awareness of G-d’s greatness, and filled with yiras Shamayim, fear of Heaven. Never have I seen anyone remotely approach his natural strength in maintaining a fear of G-d that exceeded by far his fear of man. And it is this aspect of his character and system of values that he most wanted to impart to others.

As young men in the Kollel Avodas Levi at Ner Israel, my peers and I often discussed with our Rebbe our future responsibilities as teachers of Torah. I vividly recall a particular occasion when the Rosh Yeshiva was asked about triage in teaching Torah: If we were to have one hour available per week to study with someone, how should we decide which of our students or congregants to spend it with? The Rosh Yeshiva’s response was confident and immediate: “Yiras Shamayim, fear of Heaven. You must evaluate which of your students is most likely to develop the greatest depth of fear of Heaven, and it is to that student that you must devote your energies.”

“In the end, after considering everything: Fear G-d and do His commandments, for that is what man is all about.” (Koheles 12:13)

Rebbe loved beauty and brilliance; he valued greatly wisdom, vision, and commitment. But the ultimate consideration, the measure of every student and every teacher, was, and is, yiras Shamayim, fear of Heaven. For that is what man is all about. Indeed, that was what this great man was all about. May his merit protect us and all of Israel.

Rabbi Weinberg, zt”l: An Inspiration

by Rabbi Moshe Brown

Rabbi Shmuel Yaakov Weinberg, zt”l, was an inspiration to me, and to everyone, in the sense that he was so religious in such a profound way. He was both profoundly religious and profoundly selfless. He was totally focused on his life’s mission, which was to serve as an ambassador for the honor of G-d. So, whatever he had to do – whether learning with someone at any time of day or night, or traveling to California at the drop of hat because someone needed him – he was willing to do it without the slightest concern for his own personal well being.

This attitude of selflessness was reflected in his learning as well, in how willing he was to reconsider his understanding of an inyan when a student asked a question on it. He was able to reverse his understanding, held for many decades; he did not persist in the same way just because he had assumed it to be true all that time. This emanated naturally from Rabbi Weinberg, because he was interested in truth, and in G-d’s will being implemented in the world.

I started studying with him after I was married, about 33 years ago. I was initially taken by the depth of his understanding and the penetrating insights with which he understood both learning and life. I learned with him about 10 years. Now, since his petira, I find that whenever a situation arises in my life, and I deliberate over what is the right thing to do, my first approach is to ask myself, “What would Rabbi Weinberg say?” Whether it is the proper perspective on an event that took place or on a subject I’m learning, I try to determine what his perspective would be – because it was always a very novel and a very fresh insight that he had.

Rabbi Brown is an instructor of Talmud in a yeshiva in New York.

Zeide

by Yehuda Weisbord

When I think of my grandfather Rabbi Yaakov Weinberg, zt”l, there are so many things that come to mind. His character traits, my childhood memories, conversations we had, concepts he taught – all intertwine to form the sense that I have of him. I don’t have a picture of him; a picture is limited to visual stimuli. Rather, I have a nebulous feeling, a “sense” I get when I think of him. It combines all these ways in which we related, and inevitably, it evokes a warm feeling in me. In fact, this warmth is primary in my memory; because, first and foremost, I was always aware that Zeide loved his grandchildren. That was what I knew as a young child, before I could begin to understand his wisdom, his Torah learning, his yiras Shamayim, or his devotion to the klal. And that is what was always present in every interaction that we had until the very end.

I remember how he was completely unself-conscious about this love. He, together with Bubby, ybcl”c, used to take me and my siblings or cousins on trips in the summer. I remember him meeting a talmid (student) in a park, and I noticed that he was just as comfortable as if they were in yeshiva. He did not feel that it was beneath his dignity to be taking us on those trips.

I remember the barbecues he and Bubby would make in the summer, in the house on Fallstaff Road. I remember the love in his expression when he gave us a Chanukah or birthday gift. I remember the patience he exhibited when he had to explain a mishna to me yet again, when I couldn’t quite get something.

I also remember how this love wasn’t limited to me or even to the rest of our family. I remember the warmth with which he greeted anyone who came to speak to him, and especially a talmid whom he hadn’t seen in a while. I remember the concern he had for the tzibur. Once, we were about to go somewhere – he was literally walking out the door – when the phone rang. He went back into the house and answered it, saying that maybe it was someone with a sheila. I remember the tza’ar (grief) in his voice when he heard bad news about another Yid. I have seen and heard numerous stories about how he was able to comfort people in their times of distress, simply because of the depth of warmth he communicated by his presence, his voice, and his words.

The next thing that comes to mind when I think of Zeide is his incredible way of thinking. Obviously there are talmidim more fit than I to discuss this, but as I was growing up, it gave me a tremendous sense of trust. I knew that he knew what he was doing, and that he would always make sense. I learned in many yeshivos over the years, and had many excellent rebbeim. Some them had stances on issues that did not fit in with the ideas I had heard at home. Inevitably, I always came back to this fact: Zeide made sense. He always had a unique approach, but it was always completely, solidly grounded. In fact, he himself would distinguish between what part of a thought he held was absolutely true, and what part was conjecture.

It was this completely uncompromising and utterly reliable logic that was the basis for his life. I remember him often being critical of various translations of davening or of the Torah. Many people didn’t understand why he made such a big deal out of it, but to me it made perfect sense. He based his life on his understanding of the Torah. He wasn’t frum simply because he was brought up frum. He was frum because of his understanding of the mesorah of Torah. That’s why he couldn’t bear to see anything misrepresented or misunderstood, because if Torah was distorted, then the basis for life wasn’t the same. His learning wasn’t theoretical – it was reality. I remember many occasions where he paskened (ruled on) a shaila and explained to me later that it was based on the unique way he learned a particular sugya. His lomdus (learning) wasn’t theoretical either. He lived by his understanding.

I was fortunate to spend a number of years hearing his shmuessen, shiurim, and chaburos in yeshiva. Only after his petira (passing) did I fully realize the degree to which my ideas were shaped by his teachings. Countless times, in chaburos that I was giving, his ideas came up. I find myself quoting him regularly, even now, five years since his petira. I have accepted as given so many concepts that I heard him repeat over the years. I enjoyed hearing him explain things in different contexts, to different people, simply to hear the clarity of his thoughts, and to deepen the understanding that I already had. I am grateful for the time I had with him after chaburos, or driving him places, to be able to ask and clarify ideas that I didn’t grasp. It was so wonderful to be able to turn to him with personal questions of what I should do or where I should go, and to know that his answer would give me the confidence to follow a given path.

I miss Zeide. But I know that I carry parts of him inside of me, because he has shaped me in so many wonderful ways. Most of all, I carry his love, which gives me the confidence to keep moving forward. And I carry the sense I have of him, which is both a comfort and a guide. I strive for some degree of his pashtus (simplicity), of his ability to separate the important from the trivial, and of his avdus to Hashem. With his zechus, may we all merit continued growth and the coming of the Mashiach, bb”a.

by Malka Rosenberg

I had the great privilege of speaking to the Rosh Yeshiva, Harav Yaakov Weinberg, zt”l, for eight years. Few people knew how he made himself available to speak with anyone who requested his guidance.

On many occasions, I came to his home to ask advice about schools for my children, to understand how to approach a child on specific issues, and to discuss personal matters. You had the distinct feeling as soon as you were seated that the Rosh Yeshiva already understood everything about you. His wisdom and the clarity of his thinking on any issue were simply awesome. I often wondered how he managed to give each person who came to see him such undivided attention. He made you feel he had all the time in the world, when, in reality, the phone never stopped ringing, and people were waiting outside on the porch to see him.

For myself, personally, he clarified which school would be best for each child. He stressed over and over again that a child’s success in life is built more on positive self-esteem than on getting A’s. The most amazing fact was that whatever he said would be always came true. He had a certain vision and keen understanding that enabled him to see the outcome of situations way before they happened.

The last time I saw the Rosh Yeshiva he was already quite sick. He sat and talked with me for one hour. Only afterwards did I learn how much physical pain he was in. He gave no clue as to how much he was suffering.

The essence of the Rosh Yeshiva was his profound caring. Although five years have passed, there are times I stand in my home and think, if only I could pick up the phone and call the Rosh Yeshiva. I search for answers that I think he would have said. I miss him like a father. Over eight years I had the great privilege of learning so much about life from the Rosh Yeshiva, but the most important lesson I will carry with me forever is that it is not brilliance alone that makes a human being great. It is the depth of the person’s sensitivity. The Rosh Yeshiva was a combination of brilliance, extraordinary sensitivity, and humility. I hold on to each of his words like a rare treasure.

May the Rosh Yeshiva be a meilitz yosher (interceder) for the Rebbetzin, his children, and klal Yisrael.

A Tribute to Our Rebbe, Our Spiritual Father, Rav Shmuel Yaakov Weinberg, zt'l

by Dennis Berman

It is said that a parent brings one into olam hazeh (this world), and a rebbe brings one into olam haba (the next world). It is also said that he who teaches one Torah is as if he had given birth to him. This is why we say that Rav Yaakov, as we affectionately called him, was, and is, our rebbe and our spiritual father. He found the two of us to be products of a generally assimilated background, and yet searching for our roots, eager to find a spiritual mentor who could relate to us, understand and respect our achievements in the secular world, and engage with us at a level commensurate with our intellectual and emotional capabilities. Prior to meeting Rav Yaakov, we had spoken with numerous rabbis of various leanings, and had not found the teacher we were seeking. After our initial meeting with Rav Yaakov, it was clear to us that we had met a most extraordinary individual, and although we knew virtually nothing of Torah in those days, it was patently clear to us that he was a man of tremendous learning. Over the ensuing 20 years, we would discover that he was a gadol of incredible magnitude in learning and in application. He had an incredible sense of people and a depth of feeling and sensitivity that touched the lives of thousands of people worldwide.

In the last 20 years, we have faced numerous serious challenges in our lives. In every case, Rav Yaakov was there for us in every possible way; as a guide in terms of halacha, as an enormous emotional support, spurring us on to grow with every challenge, to push ourselves in learning, in taking on mitzvot, in educating our children in Torah, in dealing with our family and professional “baal teshuva” issues. When the time and finances were in place, he encouraged us to purchase a home in Israel, and he told us that this would be one of the greatest actions that we could take to develop our family’s connection to Torah, to Israel, and to klal Yisrael, all of which have been borne out to every possible extent.

He gave us the halachic guidelines and hashkafic points of view regarding tsedaka that have formed the bedrock and bulwark for our activities in this realm.

He helped us through numerous issues of chinuch with our children. Demonstrating an ability to relate to each child, he taught us very well the dictum of “educate the child according to his way, and he will not depart from the path.”

All of the above speaks to Rav Yaakov as “rebbe.” As for the aspect of “spiritual father,” he was kind and warm; he had the most incredible twinkly eyes, and a warm, sweet, and ready smile. He was an “ish emes,” a man of truth, both as rebbe and as “father.” If he thought we were off in our thinking, he did not hesitate to say so, but always in a kind way. He also had a wonderful sense of humor. He loved to laugh, and he liked to hear us laugh. Even though he had herculean responsibilities, he was able to take pleasure in the small things. He judged himself more stringently than he judged others. He hated keeping people waiting, including his students. He always made himself available to others in every possible way, large and small.

As father and rebbe, he loved, loved, loved! to tell stories! He was a real maggid; he loved to use drama and change his voice for the effect that he could have on his listeners. He was fascinated by human nature and enjoyed sharing his observations about the greatness and the foibles of mankind in their search for G-d. He spanned the Old World and the new one in terms of his experience, breadth of knowledge, and openness to ideas. A tremendous admirer of Rambam, he also appreciated how crucial knowledge of the natural world is to the appreciation of the Creator. He was not afraid to encourage people to engage in such studies, understanding that greater knowledge could add to yirat (awe of) and ahavat (love of) Hashem (G-d). Yet it was always completely clear that Torah must be the framework for any other study, the absolute Truth that is the reality through which everything else must be viewed.

These words begin to express what our rebbe was and is to us. To say that we were blessed beyond measure to have had him in our lives for 20 years is no exaggeration. To say that we have missed him so much since his passing does not begin to address our sense of loss. Yet we feel his presence in our lives – both in the spiritual sense and in the sense of what we gained from our years of relating to him, since there is not one day in our lives, or the lives of our children which is not affected by our rebbe. He is present in every bracha that we make, in every word of lashon hara that we don’t utter, in every discussion of all things Jewish, in our choices of where we go and where we don’t go, in our communal endeavors, and in our individual journeys in learning, middot, and devekut Hashem.

This is what it is to have a rebbe, a spiritual father.

The Power of Pickled Tomatoes

by R. M. Grossblatt

It is impossible to say enough about Rabbi Shmuel Yaakov Weinberg, who died five years ago on the 17th of Tammuz. He was a gifted scholar and mentor for many. He answered questions day and night, comforted those in need, and invoked the name of God at gatherings all over the world.

At his funeral, one speaker after another praised his unselfish service. I agreed with every word I heard that somber day on the campus of Ner Israel Rabbinical College in Baltimore. Then one of his students said something that confused me.

“He never asked anything of us,” he said, “because he didn’t need anything.”

What about the pickled tomatoes, I thought.

Seven years ago, Rabbi Weinberg was visiting his family for a simcha in Atlanta. On Friday afternoon, I came to the house where he was staying and asked his daughter, my dear friend, “Do you need anything for Shabbos?”

“No, thank you,” she replied. “We have everything.”

Then I asked another family member.

She also shook her head. “Thanks anyway.”

I started walking toward the door when I heard a low, deep voice that stopped me. “You can get me something.”

I turned around and realized that the Rosh Yeshiva of Ner Israel, Rabbi Weinberg, was asking me to buy him something for Shabbos. I could hardly believe it.

“Of course!” I said, trembling with excitement. “What would the Rosh Yeshiva like?”

“You can get me pickled tomatoes.”

“Pickled tomatoes?” I repeated. “Anything else?”

“Just pickled tomatoes,” he said and smiled.

Hurriedly, I left the house, got in my car, and floated to the supermarket. I was on an errand for Rabbi Yaakov Weinberg, a man who was respected not only in Baltimore and Atlanta but all over the world. And I was going to help make his Shabbos special by providing the pickled tomatoes.

After I picked out the most expensive kosher pickled tomatoes I could find, I rushed back to the house to fulfill the rabbi’s request. For a rabbi like this, I bought not one, but two jars of pickled tomatoes and left them at the door. During the next few years, each time Rabbi Weinberg was in Atlanta, or I was in Baltimore, I tried to deliver two jars of what I thought must be his favorite food.

Once when I was out of town, I sent my oldest son. When Rabbi Weinberg opened the door and saw my son standing there clutching two jars of pickled tomatoes, he laughed loudly.

Laughter and joy were a big part of the Rabbi Weinberg’s demeanor, especially at the end of a serious conversation. He’d always lift his voice and practically sing out a blessing over the phone. I had many serious phone conversations over the years, as Rabbi Weinberg and I developed a relationship, partly due to the pickled tomatoes.

Then Rabbi Weinberg got sick. I bought several get-well cards, but every time I read them at home, I decided not to mail them. Finally, I realized that an ordinary get-well card wasn’t appropriate for a beyond-ordinary rabbi. But I wanted him to know that I cared. So I called a good friend in Baltimore who delivered two jars of pickled tomatoes from me to my rabbi – for the very last time.

Four years ago, as his first yartzeit was approaching, I thought about his funeral and the student’s comment that Rabbi Weinberg never asked for anything. Why had he asked me for the pickled tomatoes?

I recreated the scene in my mind from years before: visiting my friend, Rabbi Weinberg’s daughter, on Friday afternoon, hoping that she might need some help for Shabbos. But she didn’t; neither did anyone else. Rabbi Weinberg asked for pickled tomatoes.

Now I understood. He didn’t need them. I was the one who needed something.

Rabbi Weinberg, in his wisdom, sensed that I needed to be needed. So in the middle of a family gathering, he reached out to help a fellow Jew.

Did Rabbi Weinberg really enjoy pickled tomatoes on Shabbos? I’ll never know. What I do know is that this rabbi was more special than I realized. As the student said at the funeral, he never wanted anything for himself, only for the Jewish people.

Rabbi Yaakov Weinberg answered our questions, strengthened our belief in God, and made us feel needed. May his memory be for a blessing.

The above appeared in a past issue of Where What When