“I have no idea exactly what their fate was or how they spent their last days. I can only hope that they were together.”

With these words ended every talk that I ever heard my mother, A”H, give on her experiences in the Holocaust. But, Mommy, I now know. I’H, in a few days, I will travel to their final resting place on this earth to pay them their final respect.

Some background to this story. My mother, Emma Hubert Mogilensky, was born in Cronheim, a tiny village in Bavaria, Germany, about 2 hours north of Munich. She lived with her parents, Leo and Hedwig Hubert, and her younger brother, Selmar. When Hitler, y’sh, came to power, the waves of Anti-Semitism came to her tiny village where her family had lived for hundreds of years. She and her brother had to leave their one room village school because they were being beaten up coming and leaving school – organized by the teacher. During Kristallnacht, Leo Hubert was arrested and sent to Dachau. Their house was ransacked. After 30 days, he was released (we assume due to his medal for service in WWI), but in those 30 days he became a broken man. Hedwig had a nervous breakdown while her husband was away. There was no longer any possibility of escape for them – even had there been any place to escape to. A few months later, my mother and her family were expelled from their home – the house that my great-grandfather built. Cronheim became “Judenrein”. They fled to Augsburg, a larger town about halfway between Cronheim and Munich. There they lived, the 4 of them, in one room. My mother left on Kindertransport to England in April 1939 and my uncle in August 1939. WWII broke out a few weeks later, in September 1939. My mother was able to correspond, through the Red Cross, with her parents for a year and a half. In November of 1941, the Red Cross informed her that her parents had been transported. She knew this meant that likely they had been killed and her dreams of a reunion with the parents she loved so dearly would not be realized.

I heard this story many times growing up. As a child, I could not understand. If you only heard that they were transported maybe they did survive. It was possible. We knew several Holocaust survivors. Why couldn’t my grandparents be among them? Maybe we just needed to find them. I imagined going to Israel and finding them in Jerusalem, sitting together on a park bench, eating ice cream. Imagined how happy they would be to be reunited with my mother and to meet me and my siblings. My mother became a volunteer for the Red Cross Tracing center, an organization dedicated to helping survivors locate each other, or at least, find out what happened to their loved ones. Of course, she put in a trace on her parents. They were able to confirm that her parents had perished, but the details of how and where were still unclear. It seemed that they had been transported and killed in Riga, but it was not conclusive. And so, the matter sat for many years.

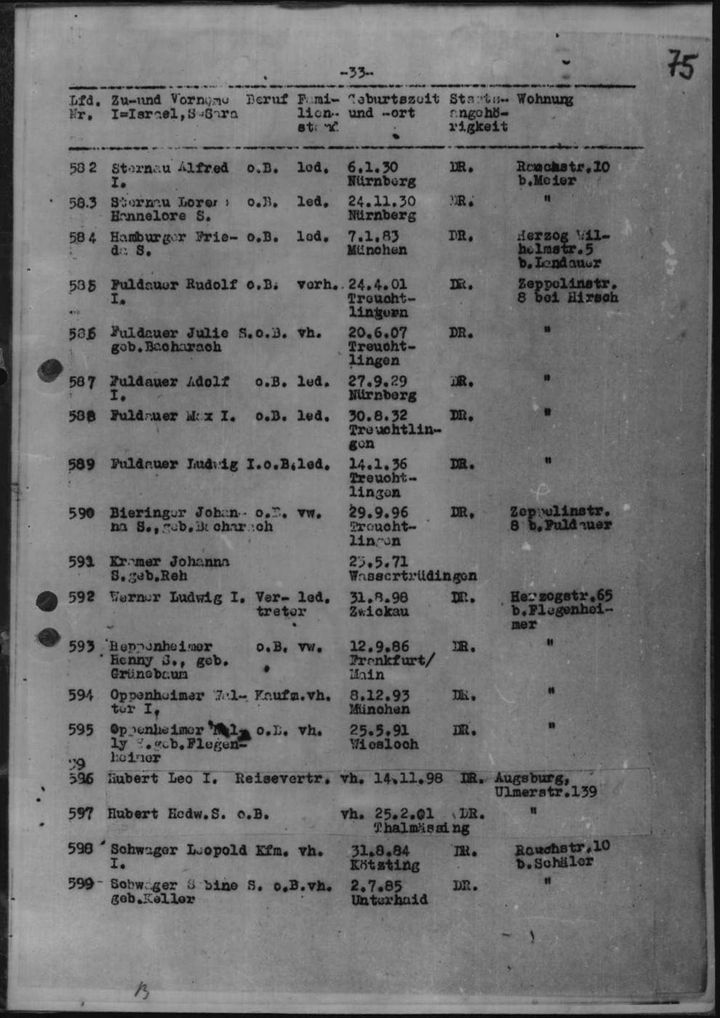

My mother passed away in July of 2015 and was buried next to my father in Eretz Yisroel. A year after she passed away, we had a startling revelation. My oldest brother, Judah, had a partner who is professional genealogist. He had started doing extensive research on our family, at Judah’s request. He was able to trace our family in Germany back over 300 years. In researching, he came across the records from a transport on November 20, 1941 to Fort IX outside of Kovno (modern-day Kaunas) in Lithuania. My grandparents’ names were on the manifest. Everyone on that train was taken off and shot at Fort IX five days later November 25, 1941. So then, seemed to be conclusive proof of their fate. But so odd. Why would they have been taken to Kovno from Germany? Despite not understanding how this occurred, from the time that I first heard the news, I was consumed by the thought that I must go there. One time. To see where they are buried. To show them that they are not forgotten. To tell them that their family, their heritage, their Yiddishkeit lives on. My mother was not allowed this knowledge of their final burial place in her lifetime. Perhaps the knowledge would have been too hard for her. But if Hashem had allowed us to find out, I felt it compelled me to action.

I did more reading and more research. And I found the answers to what had happened.

The Ninth Fort massacres of November 1941 were two separate mass shootings of 4,934 German Jews in the Ninth Fort near Kaunas, Lithuania. These were the first systematic mass killings of German Jews during the Holocaust. In September of 1941, Hitler decided that the 300,000 Jews of German, Austrian or Czech nationality should be deported from Germany by the end of the year. These Jews were known as Reich Jews, Jews of the Reich countries – as opposed to Ostjuden, the Jews of Eastern Europe. From October 15 – Feb 21, 58,000 Reich Jews were transported. These transport trains consisted of 1000 people each. No death camps existed in the Reich countries – concentration camps but not death camps. So, the destination for these trains was instead to be several ghettos which already existed in Eastern Europe. Originally, the destination of these trains was Riga, Lodz and Minsk. The first 25 trains were to go to Riga. However, the Germans in charge of the Riga ghetto did not want these 25,000 Jews. In November 1941, it was decided that five of the of the 25 trains that were supposed to go to Riga would instead go to the Kovno ghetto. These were the first 5 trains and were in fact already on the way to Riga. They had left from Berlin, Frankfort, Vienna, Breslau and Munich between November 13th and the 23rd. My grandparents were on the train from Munich. But, upon arrival in Kovno, the decision was made by Karl Jager, the head of one of the Einsatzgruppe A subunits (Einsatzgruppe A was one of 3 Einsatzgruppe units, each was allocated a different area of Eastern Europe to kill Jews) to take the Jews off the trains and shoot them immediately at Fort IX. There were 2 separate shootings on November 25th and the 29th. In the November 25th shootings, 1,159 men, 1,600 women and 175 children from Berlin, Munich and Frankfort were killed. Among them were my grandparents. Had my mother and uncle not left on the Kinderstransports to London when they did, it would have been them as well.

So, I knew I wanted to go. It could only be a summer trip, given the harsh winters of Lithuania. For various reasons each year, it wasn’t possible to do it. But this year, I didn’t see any obstacles. After researching, I decided that we needed to be based in Vilna. Vilna has a shule and a kosher restaurant and a major airport. It is only 1.5 hours to Kovna. Working with the incredibly helpful staff of Chabad of Lithuania, I found a guide/driver and a hotel within walking distance of the shule. I booked flights for myself and my husband. My oldest brother, Judah, also booked his flights so that we could do this together. Especially meaningful since he is named after my grandfather and my middle name is the name of my grandmother.

One week before the trip, I went to the Beis Hakvoros where my parents are buried. After reciting the prayers said by the kevorim of a father and a mother, I sat down on the ground, lay my head on my mother’s matzeivah and told her what my plans were. Then I cried. I cried because she never knew what I now know. I cried because this is such a sad journey that I must make, to see the final resting place of my grandparents whom I never had the privilege of knowing, who were murdered 15 years before I was born. And of course, I cried because I miss my mother so much, a mere 4 years after her death.

We arrived late Monday night. Tuesday morning, we spent touring the Jewish history of Vilna. Tuesday afternoon we went to the Vilna cemetery, current location of the kever of the Vilna Gaon and the Ger Tzedek, as well as many other talmidei chachamim. Then we went to Ponary. The site of mass murders of 70,000 Jews, including the Jews of Vilna. A beautiful peaceful dense pine forest. With seven pits of mass murder. As our guide explained, even then the Jews had no peace. Starting in 1942, Himmler ordered that all the dead bodies of the Jews were to be exhumed and burnt to conceal the evidence of the murders. Suddenly, I was hit by a hard realization. My grandparents’ bodies were not in a mass grave. What happened at Ponary also happened at Fort IX. I could visit the spot where they died, but there would be nothing else there.

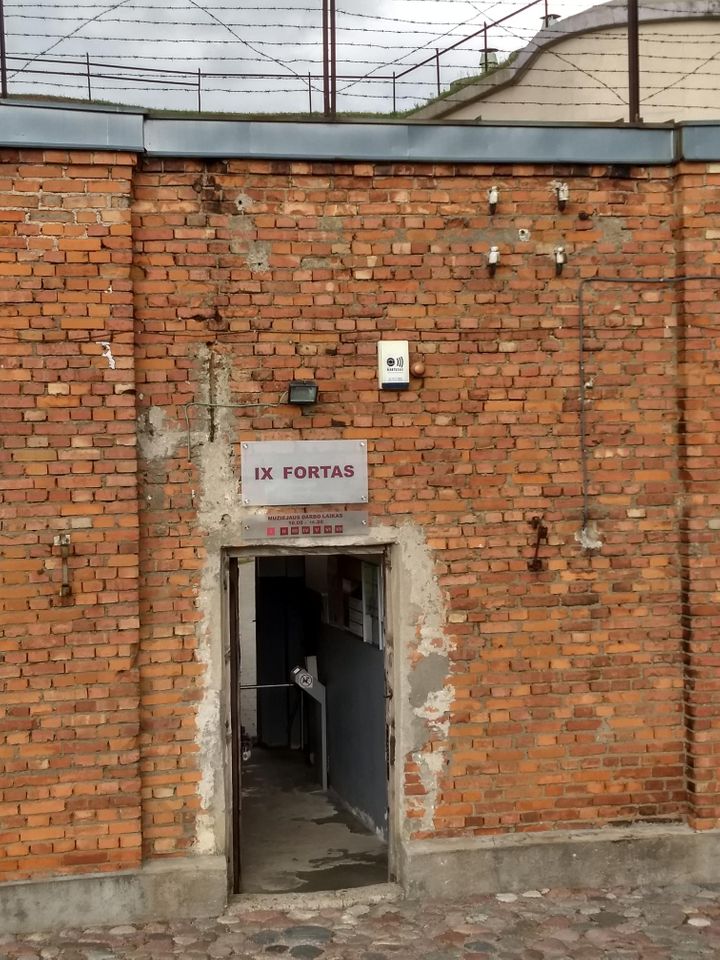

On Wednesday, we visited a typical Lithuanian shtetl, Žiežmaria. Before the war, the shtetl was 75% Jewish. Today, of course, there are no Jews at all. However, in this shtetl, the wooden shule had not been burnt down. It had been in extremely run-down condition but in 2016, two of the families of the shtetl decided to work on its restoration. We were able to visit the shule and it was easy to imagine how it had been once. It is one of only 7 surviving wooden shules in Lithuania. From there we went to Kovno (modern day Kaunas). I became increasing tense and was unable to really focus on anything our guide was showing us. All I could think about was getting to Fort IX. We arrived and toured the fort itself which was used to house some prisoners, but mostly, the victims were shot outside, immediately on arrival. Notable exception was the group of 62 people who were tasked with the uncovering and burning of the 45,000-50,000 Jews who had been murdered there. There was a hall recording histories of people who died at Fort IX, and a hall of survivors of the Kovno ghetto. One beautiful hall commemorated Lithuanian non-Jews who risked their lives to save Jews. Notable in this hall was the section devoted to Chiune Sugihara, the Japanese consul-general in Kovno. In defiance of Japanese policy and explicit orders, he issued thousands of visas to Jews fleeing German-occupied Poland and Lithuania. Even as he waited at the train station for the train to return him to Japan when his government recalled him, he continued to write visas by hand and stamp them.

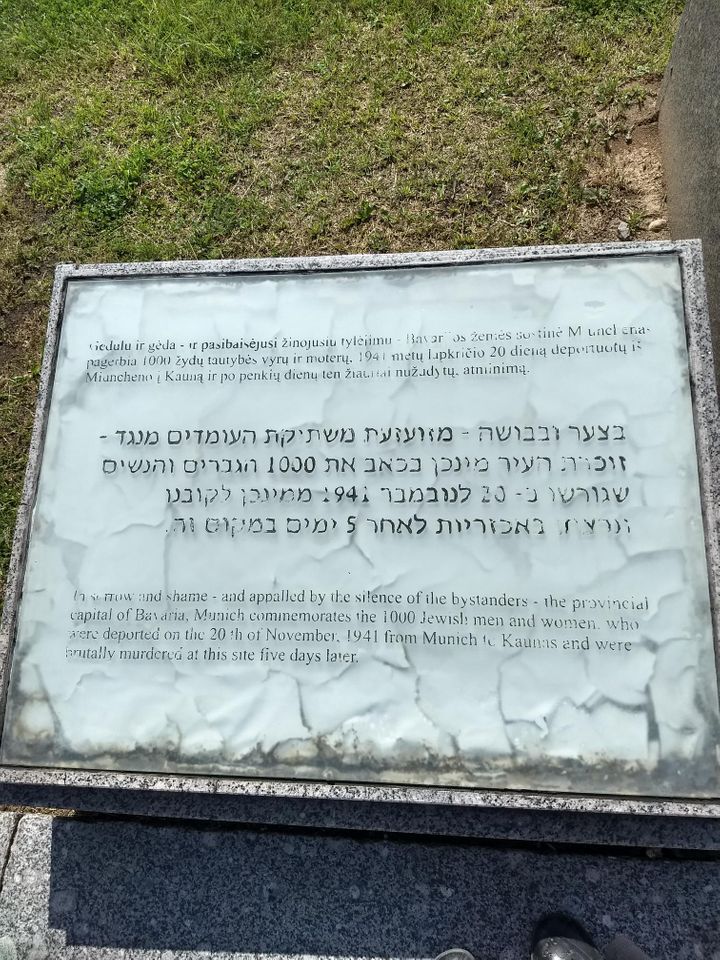

Finally, we went outside the fort. To see the place where the murders of 50,000 Jews took place, including my grandparents. It’s a large grass field bordered by the walls of the fort. No evidence of any kind to show what happened there. The area is now ringed by plaques, in various languages, erected to commemorate the various groups of Jews murdered there. And there, written in Lithuanian, Hebrew and English, was the one plaque I needed to see and touch. The only tangible presence of my grandparents.

In sorrow and shame – and appalled by the silence of the bystanders – the provincial capital of Bavaria, Munich commemorates the 1000 Jewish men and women who were deported on the 20th of November 1941 from Munich to Kaunas and were brutally murdered at this site five days later.

I knelt and touched the words. I whispered to my grandparents that they are not forgotten and that their family lives on and follows in the ways of Hashem and His Torah. I was able to recite the prayers said by the kever of a grandfather and a grandmother for them for the first and the last time. Even though I knew there really was no kever to speak of there. I had come and accomplished what I had set out to do. As painful as it was to be there, I walked away with a lighter heart. I would never return there, as there is nothing more to add. Only one task yet remained. To go back to my mother’s kever and tell her what we saw and did.

Once it was time to leave, early on Thursday morning, I couldn’t wait to get out of Europe.. We arrived back early on Thursday afternoon. I was so struck by the contrast. Eastern Europe with its Jewishness in the past, cut off so tragically. Israel with its Jewishness in the present and the future.

The mashal is told of a husband and a wife who loved each other dearly but were not blessed with children. After many years of waiting, they were finally expecting a child. At the delivery, the doctor told the husband that things were going very badly. He could save either the wife or the child, but not both. The wife was consulted, and she chose to give life to the child they had waited so very long for. A healthy son was born, and the wife passed away. 13 years later was the bar mitzvah of this son. At the luncheon, the father spoke lovingly and with great sorrow of his wife, the boy’s mother. All the relatives cried. But not the son. He sat there, dry-eyed. His aunt came to reprimand him. “How can you not cry for the mother who died giving birth to you?”, she scolded him. His reply was chilling. “You all knew my mother. You had a relationship with her. You knew who she was. I never had the privilege. How can I can cry for someone I never knew? For a relationship I never had?”

The mashal is brought to explain the difficulty we have properly mourning the destruction of the Beis HaMikdash. We never saw it. We never experienced what it was like to have it. So how can we properly mourn its loss? In much the same way, I feel I never properly mourned the loss of my grandparents, since I never knew them at all. Until now. Immersing myself in their story and going to where they were murdered made me feel connected to them in a way that I never had before. As Tisha B’Av approaches, may we learn what we have lost, in so many ways, with the destruction of our Beis HaMikdash. In that merit, of truly mourning that what we have lost, may Hashem bring Moshiach soon and bring all Jews home where we truly belong. May our long and painful galus finally come to an end.

And, may I be zocha to finally meet my grandparents whom I never knew.

Dedicated in memory of Yehudah ben Reuven and Chana bas Shlomo. Hashem yikom damom.

Also dedicated in memory of my mother, Malka Sarah bas Yehudah, a'h, whose yahrzeit is today, the 17th of Tammuz and has been reunited with her beloved parents

Restored Wooden Shule - Ezras Nashim

Restored Wooden Shule Bima

Restored Wooden Shule Outside

Fort IX Outside

Fort IX Sign

Killing Area in Fort IX Compound

Memorial at Fort IX

Plaque at Fort IX

Marker of Kovno Ghetto Gates

Train Manifest Document