A brief introduction is in order so as to explain why I chose this topic for this week. A few years ago, as a kohein, I had to change my travel plans, and instead of flying from Ben Gurion airport to Newark, I had to fly via Haifa to Larnaca, Cyprus, and then to London and Reykjavik to reach my destination. The trip whetted my appetite to find out more about Cyprus, and this article is a result.

Those who want to read about that trip can access From Haifa to Reykjavik on the website RabbiKaganoff.com. Since this week’s parsha includes most of the laws of tumas meis, which was the reason why I needed to travel via Haifa, I decided to share this article.

Question #1: When in Crete, do as the Cretans do?

“I was told that when I am in Crete, I should separate terumos and maasros from the vegetables and avoid the fruit, because of concerns of orlah. Is this halachically accurate?”

Question #2: Which esrog?

“Is it better to use an esrog from Corfu, from Corsica, or from the mainland in between?”

Question #3: Which minhag should I observe?

“I am of Greek/Sefardic background, but my immediate ancestors were not observant. Should I follow Sefardic custom or Greek custom?”

Introduction:

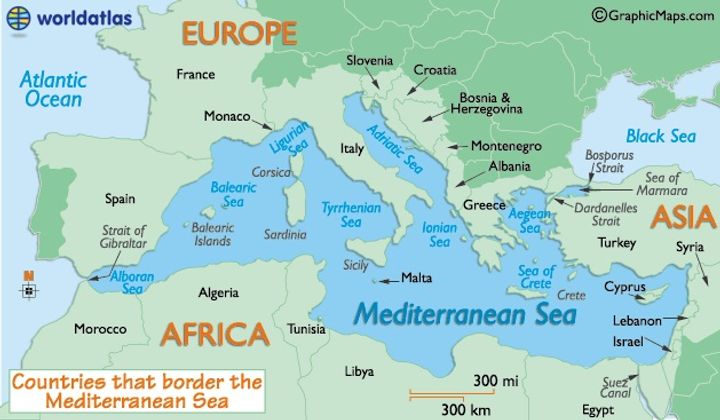

Among the many beautiful islands that grace the Mediterranean Sea, we will discuss four whose English names all begin with the letter “C.” Although none of these four – Corfu, Corsica, Crete and Cyprus – is currently home to a sizable Jewish community, at one time each figured significantly in Jewish history. I’ll provide a short description of the location and history of each of these islands, and then address the unique role that each had in Jewish history and halacha.

Cyprus

The largest of these four islands, Cyprus, is the third largest island in the Mediterranean. (The two largest islands in the Mediterranean are Sicily and Sardinia. Although they are both sounded with what phonetics calls a “soft ‘c’,” since both islands are spelled in English with the letter “s,” we will discuss their halachic significance in a different article.) Cyprus is located only forty miles south of Turkey, east of Greece, west of Syria and Lebanon and north of Egypt. Of the four islands that we are discussing, it is the closest to Eretz Yisroel, with a distance of less than three hundred miles.

Jews in Cyprus

We know of Jews living in Cyprus as early as the time of the Chashmonayim, over 2200 years ago. The Jewish population of Cyprus has waxed and waned; at times there was a substantial Jewish community there. When the traveler Binyamin of Tudela visited the island in the 12th century, he discovered three Jewish communities: a halachically abiding kehillah, a community of Kara’im, and yet another group that kept Shabbos from the morning of Shabbos until Sunday morning but desecrated it on Friday night.

Neither Sefardim nor Ashkenazim

Although historians usually group all Jews into either Sefardim or Ashkenazim, this categorization is simplistic and inaccurate. For example, there are several different groups of Italian Jews who are neither Sefardim nor Ashkenazim, but have their own distinct customs and practices. Similarly, although the Jewish communities of twelfth and thirteenth century Provence (southern France) are often referred to as Sefardim, they followed practices of neither Sefardim nor Ashkenazim but had their own unique way of doing things. For example, they began reciting vesein tal umatar on the 7th of Marcheshvan, which is the practice of Eretz Yisroel and not of either Sefardim or Ashkenazim in chutz la’aretz.

Greek Jews

The original Jewish population of Cyprus followed neither Ashkenazic nor Sefardic practice, but rather the very distinctive practices of the ancient Jewish communities of Greece, which is called Romaniote (not to be confused with Roman or Romanian; According to my research, the origin of the term Romaniote goes back to the days when they were part of the Eastern Roman Empire, usually referred to as the Byzantine Empire, after the fall of Rome.) They have their own unique nusach hatefillah, their own tune for reading the Torah and many other halachic practices that are different from both Sefardic and Ashkenazic custom. At one time in history, the customs of the Romaniote communities were widespread throughout Salonika, Athens, and other places in mainland Greece, and among the various Greek islands, including Cyprus, Crete and Corfu. However, the massive influx of Sefardic Jews after the Spanish expulsion caused many of the Greek communities to adopt Sefardic practices. Today, few communities, if any, left in the world follow the Romaniote nusach, although some Romaniote practices are still observed by some shullen in places as diverse as Eretz Yisroel and New York.

One common Romaniote shul practice is that Aleinu is recited not at the end of davening, but at the beginning. Another is that the shulchan for reading the Torah is placed towards the back of the shul, not in the middle.

Corsica

Corsica is the fourth largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, located due west and very close to the Italian Peninsula. It is probably most famous for its native son, Napoleon Bonaparte. Historically, it has been ruled by Greeks, Romans, Goths, Byzantines and Arabs; and later by Pisa, Genoa and many others. French rule is relatively recent, only since the 18th century, and the original, native Corsican language is really a dialect of Italian. Although Corsica is legally part of France, it is both physically and culturally much closer to southern Italy than to France. For this reason, there is a troubled relationship between the French mainland and Corsica, which benefited the Jews during World War II, as we will soon learn.

Corsica was the last of the four Mediterranean islands of our article to have an organized Jewish community. Nevertheless, there is some relevant history related to Jews and Corsica, which we will discuss shortly.

Crete

Crete is the fifth largest island in the Mediterranean and the largest and most populous of the islands of Greece. It is located southeast of mainland Greece, in the southern part of the Aegean Sea, and it is less than 600 miles from the coast of Eretz Yisroel.

Crete’s known archeological history is possibly the most ancient in the world – it dates back to the time of the dispersion after Migdal Bavel. Later, Crete was the home of the ancient Minoan civilization. Afterward, it became part of the Roman Empire and then the Byzantine Eastern Roman Empire. It was conquered by the Arabs, the Crusaders, and in 1204, by the Venetians, who ruled it for over four hundred years, until it was conquered by the Ottoman Turks. Muhammad Ali (the founder of the modern Egyptian dynasty, not the boxer) desired control over it as payment for his military services to the Ottoman Empire in the Greek Rebellion (1820s), in which case it would have become part of Egypt, but he did not succeed in procuring the island.

Jewish Crete

It is known that there was ongoing Jewish settlement in Crete since the times of the Maccabees. Crete’s Jewish community was existent from the time of the destruction of the Beis Hamikdash until the era of the Nazis, but by 1941, most Jews had moved to Athens or Salonika, both of which are in mainland Greece. When the Nazis conquered Crete, less than 400 Jews were known to be on the island. Unfortunately, my research indicates that they were all killed in the war.

Halachic Crete

At this point, we can address one of our opening questions: “I was told that when I am in Crete, I should avoid eating locally grown fruit because of concerns about orlah and be careful to separate terumos and maasros. Is this halachically correct?”

The laws of terumos and maasros apply min haTorah only in Eretz Yisroel, and the laws of orlah, the fruit that grows during a tree’s first three years, are far more stringent in Eretz Yisroel than they are in chutz la’aretz. It is therefore important to know whether something grew in Eretz Yisroel or in chutz la’aretz.

It is fascinating to note that, according to a minority opinion among the tanna’im, both Crete and Cyprus have the halachic status of being part of Eretz Yisroel (see Gittin 8a and Tosafos ad locum). Allow me to explain:

In Parshas Masei, the Torah describes the western border of Eretz Yisroel:

The western border will be the Great Sea, and its territory [“ugevul”]; that will be for you the western border. (I have followed the translation of Rav Samson Raphael Hirsch that the word gevul means its territory.) According to the Gemara (Gittin 8a), the word ugevul teaches that there are islands in the Mediterranean, the “Great Sea” of the pasuk, that are halachically considered part of Eretz Yisroel. There, the Gemara quotes a dispute between tanna’im regarding which islands located in the Mediterranean are halachically part of Eretz Yisroel and which are not. Rabi Yehudah contends that the word ugevul includes any island in the Mediterranean situated directly west of Eretz Yisroel. These islands are imbued with the sanctity of the Holy Land. Since, according to some opinions, the Biblically promised area of Eretz Yisroel extends quite far north, many of the southern Greek islands, including both Cyprus and Crete, are halachically Eretz Yisroel, according to Rabi Yehudah.

However, we do not follow this approach, but that of the rabbonon. They draw an imaginary line from the northwestern-most point of Eretz Yisroel to its southwestern-most point and include only islands that are east of this imaginary line. There are few islands in this area, and certainly both Cyprus and Crete are not included (Derech Emunah, Terumos 1:89).

Corfu

Corfu, by far the smallest of the four islands we are discussing, is today part of the country of Greece. It is on the opposite side of Greece from Crete, northwest of the Greek mainland; the second largest and most northern of the Ionian Islands. On the above map, Corfu is too small to be identified, but the island in the northeastern corner of the Ionian Sea, near the border of Greece and Albania, is Corfu.

Jews of Corfu

The 12th century Jewish traveler, Binyamin of Tudela, writes that he crossed the Ionian Sea from Otranto, Italy, to Corfu. From Corfu, he sailed to Arta on the Greek mainland, and from there he traversed the rest of Greece. In his day, there was no Jewish community in Corfu, but it appears that about a century after his trip, there was what we can call a “Jewvenation” of the island. It appears that Jews arrived there from Greece to the east, and from Italy to the west. The communities of southeastern Italy (the heel of the Italian boot) – again, neither Ashkenazim nor Sefardim – had their own customs, which were usually called Puglian, taken from a geographic term applied to this area of Italy. (In English, this area is usually called Apulia.) The Puglian Jews trace their history in the Italian boot to the time of the Second Beis Hamikdash, when Jews often settled in Italy as a result of the increasing influence of the Roman Empire.

Apparently, there were two different communities in Corfu, each with its own shul and its own cemetery. After the Spanish expulsion, a new ingredient was added to the Corfu mix, when the Sefardic Jews arrived. Thus, there were three distinct kehillos in this relatively small community: Romaniote, Puglian, and Sefardic. Still later, I found reference to a fourth kehillah in Corfu following the customs of the Sicilian communities (Shu”t Haredach #11). In a relatively unknown chapter of Jewish history, there was a vibrant Jewish community in Sicily (which begins with an S, not a C) that was expelled in 1492, at the same time the Jews were expelled from Spain.

As a result of this interesting background, the Jews of Corfu spoke their own distinctive local dialect, a mixture of Greek, Hebrew and Italian. This language was distinct from that of other Greek Jews, who spoke their own dialect of Greek called Yevanic. (Think of the relationship between German and Yiddish.) The Corfu Jews were the only significant minority among a population that was otherwise exclusively Greek Orthodox.

Of the four islands that we have discussed, Corfu contained the most prominent Jewish community, including many prominent rabbonim and poskim. For example, in the early sixteenth century, the Shu”t Binyamin Ze’ev refers to the city of Corfu as boasting of a resident, Rav Shabsi Kohen, as a great talmid chacham among a community of talmidei chachamim. We have extant a heter agunah signed by this Rav Shabsi together with two other local rabbonim in the year 1510.

Not long thereafter, the rav of the Romaniote kehillah of Corfu was Rabbi David ben Chaim Hacohen (the Radach) a prominent posek who corresponded with the great Sefardic poskim of his time. He may have had a yeshiva there, since the author of Teshuvos Mishpetei Shmuel calls himself a disciple of Rabbi David ben Chaim Hacohen.

Corfu is mentioned in the context of various halachic issues in hundreds of responsa. At one point, it even boasted its own Jewish printing house.

By the nineteenth century approximately 5,000 Jews lived on the island, each affiliated with one of the various kehillos. In the course of time, the Sefardic community became the strongest and, although the other shullen were still called the Greek, Puglian or Sicilian shullen, they all davened the nusach of the original Spanish communities.

The unfortunate destruction of this once-vibrant community occurred in two stages. In the late nineteenth century, there was a blood libel, the result of which was that the majority of the Jewish community dispersed to other lands. Of course, the final blow was the Nazis, who wiped out virtually the entire remaining population of about 2,000 Jews. Today, there are less than one hundred highly assimilated Jews on Corfu among a population of about 100,000 people, and only one shul is known to still exist.

Corfu esrog

Corfu’s semi-tropical climate allowed it to make a unique contribution to Jewish history. For well over a century, it was the primary source for esrogim used all over Europe. Corfu esrogim, which were apparently predominantly grown by non-Jewish farmers, were known for their beauty. Since they were grown by non-Jews for the Jewish market, there was much halachic discussion, beginning as far back as the 18th century, concerning whether one could rely that the esrogim had not been crossbred with other species, which would invalidate them according to most opinions. (Discussions about crossbred esrogim date back to the sixteenth century, with the majority of halachic authorities ruling that one cannot fulfill the mitzvah on Sukkos with an esrog grafted onto a tree of another species.) One very prominent authority, the Beis Meir, invalidated the Corfu esrogim (responsum at the end of the Orach Chayim volume of his commentary to Shulchan Aruch), while others ruled that they were kosher (Shu”t Beis Efrayim, Orach Chayim #56; Shaarei Teshuvah 649:7; Shu”t Zecher Yehosef #232).

Corfu vs. Corsica

Esrogim also grow on Corsica, which is on the other side of the Italian peninsula from Corfu. At one point, these three areas, the two islands of Corfu and Corsica, and the Italian mainland in between, were the main sources of esrogim shipped to central and Eastern Europe. Toward the end of the nineteenth century, we find various disputing responsa regarding which esrogim were acceptable or preferable. Some authorities ruled that one may use the Corfu esrogim but not those from Corsica, while others ruled just the opposite (Shu”t Tuv Taam Vadaas, #171; Shu”t Rabbi Yitzchak Elchanan Spektor #28; also see Shu”t Sho’eil Umeishiv, Mahadura Telisa’i #144; Shu”t Or Somayach 2:1; Shu”t Tzitz Eliezer 10:11:7). Still others ruled that both of these varieties of esrogim were kosher, but that it was preferable to purchase only from Eretz Yisroel, where the modern business of growing and shipping esrogim was just beginning (Shu”t Yeshuos Malko, Orach Chayim #46; Shu”t Avnei Neizer, Choshen Mishpat #115).

In 1875, we have recorded the following halachic inquiry: An esrog retailer in Poland received esrogim from Corsica, and wanted to return them to his distributor, claiming that he had always previously received esrogim from Corfu. Is the buyer entitled to a refund?

Shu”t Beis Yitzchok rules that he is entitled to get his money back. Since the esrogim sold in that area were from Corfu, the distributor was required to tell the retailer that the esrogim were from a different source before he shipped them (Orach Chayim #108).

At this point, we can answer the second of our opening questions: “Is it better to use an esrog from Corfu, from Corsica, or from the mainland in between?”

The answer is that in the 21st century, most authorities will tell you to purchase an esrog grown in Eretz Yisroel. In earlier times, there were halachic disputes about the subject.

Corsican salvation

I mentioned earlier the troubled relationship between the French mainland and Corsica, from which the Jews benefited during the Holocaust. During World War II, France was divided into Nazi-occupied northern France, and the collaborative Pétain government, colloquially referred to as Vichy France, named for its capital. (Paris was occupied by the Nazis.) Mainland France under Marshal Pétain organized a census of its Jewish population that was subsequently used to hunt thousands of Jews who were rounded up, placed on trains and sent to the death camps. The remaining French Jews tried frantically to find shelter with those comparatively few sympathetic French people who were willing to hide them. Many fled to Corsica, where a small Jewish community existed.

Post-war historians have discovered documents from France’s Vichy government archives that imply that relatively few Jews were turned over by the non-Jewish Corsicans. According to recently published magazine articles, the Corsicans' hatred of the French was put to good use, as the Corsicans kept the Jewish presence a secret from prying French eyes. The Corsican authorities’ explanation for not handing over any Jews was that there were none on the island. This explanation was accepted by Vichy, because the mainland, too, widely believed that hardly any Jews were in Corsica. In fact, thousands of Jews survived the war there.

Thus we see that, although none of these islands has a significant Jewish community, each was important at one time. Perhaps of greatest interest is that although Corsica’s community was always small, it ended up being a refuge that saved thousands of Jewish lives. Hashem rules the world and clearly destined that each of these islands fulfill a role in Jewish history and halacha.