Of all the various laws enumerated in our portion, there is one that stands out, not only because it is the sole one that has a very specific consequence, but for the extremeness of the punishment.

One who causes pain to a widow or orphan, prodding them to cry out to G-d, is assured they will be responded to quickly.

Addressing the perpetrator, G-d vows, "My wrath shall blaze, I shall kill you by the sword, and your wives will be widows and your children orphans." (שמות כב כג)

This retribution, although depicted in the context of these most vulnerable individuals, applies equally to all the downtrodden who are victimized by others. (רש"י שם)

Rashi points out redundancy in the verse. If the Torah reports that the offender will die, isn't it self-evident that his wife and children will become widowed and orphaned, why is it necessary to state then ' your wives will be widows and your children orphans'? Quoting the Talmud, he adds, that this intimates an added layer of curse, namely, that the wives will be bound in living-widowhood — there will be no witnesses to their husbands' deaths, and [thus] they will be forbidden to remarry. The children will be orphans because the courts will not allow them to have their fathers' property, since they do not know whether they died or were captured.

This tortuous state of 'living in limbo' is unique to this command alone.

Despite this penalty of premature death being like the many other sins in the Torah that do not warrant a death penalty at the hands of a Jewish court, only through heaven, which are generally classified under the heading of transgressions that are punishable by מיתה בידי שמים — Death at the Hands of Heaven, this one is never enumerated throughout the Mishna or Talmud as such.

Why not?

The Talmud makes a most startling assertion.

Both the one who cries out and the one about whom he is crying out are included in the verse discussing the cries of the one who is mistreated: “If you afflict them, for if they cry at all to Me, I shall surely hear their cry. My wrath shall blaze, and I shall kill you with the sword”. (ב"ק צג.)

Rashi explains that this is indicated in the Torah's description of G-d's wrath towards the victimizer and His vow of והרגתי אתכם — I shall kill you, being in the plural, referring not only to victimizer but also to the victim who is depicted in the verse immediately prior as the 'צעק יצעק' — Who shall cry out [to Me].

Although G-d also promises שמע אשמע — I shall surely hear [the cry], nevertheless the widow or orphan 'who cries out' may also be punished!

The Talmud furthermore adds: But they are quicker to punish the one who cries out than the one about whom he is crying out.

This is derived from the incident of Avraham and Sarah. Rabbi Chanan says: One who passes the judgment of another to Heaven is punished first, as it is stated: "And Sarai said to Avram: My wrong be upon you, I gave my handmaid into your bosom; and when she saw that she had conceived, I was despised in her eyes: The Lord judge between me and you" (Bereishis 16 5). Sarai stated that G-d should judge Avram for his actions. And it is written:" And Avraham came to mourn for Sarah, and to weep for her" (Ibid. 23 2), as Sarah died first.

Sarah takes Avraham to task, firstly, for not including her in his prayer to have a child, and secondly, for not defending her in the face of Hagar belittling her after she becomes pregnant and questioning the still barren Sarah's worthiness.

The Midrash reports that Sarah lost 48 years of her life because of her 'throwing down the gauntlet' and asking G-d to judge between them.

The Talmud adds that one may not ask G-d to judge another person — lest they be held accountable as well — only when there are other alternatives available. Some explain this to mean that Sarah could have lodged her plaint first with the court of Shem, the illustrious son of Noach, who was yet alive, who might have mediated between them. Others suggest that perhaps she should have first sought to discuss her issues with Avraham first, before summoning him to judgment before G-d. (תוספות והר"ן)

What is perplexing is Rabbi Yitzchok's equating the abused widow's cry to G-d for help with the episode with Sarah, and by association blaming the poor widow for tasking her tormentor and reaching out to G-d for intervention. Is there any evidence she wants the abuser punished? She in desperation is simply passionately praying to G-d to resolve her plight.

When one becomes the victim of someone else's cruelty are we truly not deserving of that pain? Does G-d ever allow anyone to suffer lest they deserve it or need it to prod them towards greater character and self-perfection?

Of course, one must defend oneself and not simply beg to 'bring on the pain', but might there be something theologically wrong in simply expecting G-d to do away with the perpetrator and expect that to solve the abuse?

There exists an operative מדת הדין — Attribute of Justice that governs the world. We are responsible for every infraction we make and will be held accountable. No one can harm us unless it is so destined.

But there is an even greater operating system that exists, the מדת הרחמים — Attribute of Compassion, that tempers that of judgment.

When man is not self-absorbed, and is attentive and sensitive to others, the kindness that extends outward from that core can mitigate the operative force of judgment.

Perhaps Sarah understood quite well that when Avraham prayed for himself, she was included — since he saw her as the 'other side of his own coin' — but it wasn't expressed. She also sensed that Avraham cared for her deeply and wasn't ignoring her pain but was acting as a true believer knowing that Sarah would deal with the 'deck of cards she was dealt' — which was no accident and meant to prod her to greater heights of devotion — and aptly handle with aplomb.

But Sarah knew that living in the realm of the Attribute of Judgment is an arduous challenge. People are human and frail, they need to be buoyed by warmth and kindness. If we succeed in creating a 'friendlier world' in the spirit of the Attribute of Compassion, we will lift each other up, fortifying one another, without the need for Divine intervention, which stokes the Attribute of Judgment, placing even the victim under the microscope of judgment and worthiness.

Sarah knew her marriage to Avraham would inspire all their progeny for eternity.

She willingly forfeited 48 years of her life to assure that no spouse would ever lapse in dangerous self-absorption, neglecting to be sensitive to the other.

A man who is so wrapped up with himself to be indifferent to the vulnerable widow and orphan, who are isolated and helpless, causing them pain, will be punished that he will fall to the sword of the enemy, leaving his wife and child powerless. They will face, due to the lack of evidence of his death, eternal limbo, remaining neglected and without access to resources.

The severity of this punishment is the natural consequence of a world inhabited by people who cannot see beyond their own needs, incapable of identifying with those weak and alone.

The portrayal of this terrible state is instructive in informing us that the only way we can prevent the world from descending into the harsh reality of judgment, is if we create a world of empathy, sensitivity, and kindness that will rekindle a brilliant atmosphere of compassion.

There must never be a situation where one cries out at having been pained by one's fellow man. Calling out to G-d to be saved from an oppressor is a dangerous tool for it awakens the world of judgment that scrutinizes the crier as well, questioning whether the crier deserves to be relieved, and places oneself in greater jeopardy than the tormentor.

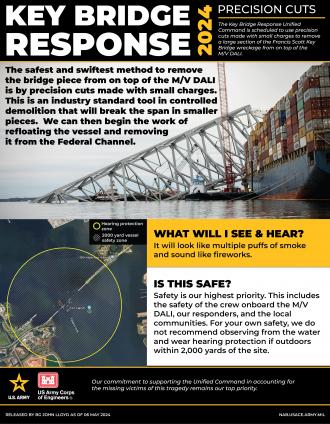

We are living through a period of history for our people where many wives and children are living in limbo, paralyzed in time, not knowing the fate of the hostages — their husbands; wives; children; parents.

We as a collective must wake up from our living in limbo, and take a hard look at the people around us and determine whether we are creating an atmosphere of compassion and sensitivity, and are not wallowing mindlessly in the empty distractions we often engage in.

This is the only antidote we have, to inspire in Heaven a bounty of compassion, restoring all our loved ones to the warm embrace of their families and nation.

באהבה,

צבי יהודה טייכמאן