Posted on 02/26/18

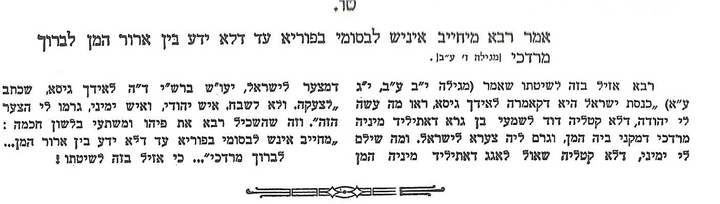

Rava said, It is one’s duty levasumei, to make oneself fragrant [with wine] on Purim until one cannot tell the difference between ‘arur Haman’ (cursed be Haman) and ‘barukh Mordekhai’ (blessed be Mordecai)

- Babylonian Talmud, Megillah 7b

Over the centuries, the “duty” to make oneself “fragrant” (drunk) on Purim has represented the great example of “the exception proves the rule” when it comes to Jewish practice. After all, while we Jews have been accused of many things over the centuries, no one has ever suggested that we do not strive to distinguish between good and evil. In fact, making that distinction between good and evil, right and wrong is essential to who we are. We are also well known for moderation in our lives. We enjoy wine and use it to sanctify many of our most dearly held rituals. But drink wine to get drunk? Never.

So, this “duty” seems to contradict essential Jewish behaviors and, in doing so, it has rendered Purim into a holiday associated with drunkenness, partying and revelry. Many modern Jews confuse Purim as a “Jewish Halloween” or an excuse for wild parties. Like carousers at a masquerade, this view has us put on masks, to “hide” who we really are.

Or, perhaps, as often proves to be the case at a masquerade, we don masks to reveal who we really are.

* * *

The common understanding of Rava’s pronouncement is so embraced that the pious and the wise have, for centuries, twisted themselves in knots to make sense of it. My beloved grandfather, Rav Bezalel Zev Shafran, was not satisfied with the common understanding. His comments about the Purim story invite us… demands of us! … that we delve deeper into the story if we are to truly understand Rava’s intent and, in the process, embrace something vital about the observance.

My grandfather, in questioning the common understanding, notes that the very same Rava who posits this extraordinary directive further differs with his fellow sages just a few dapim later. In Megilah 12b-13a, the Talmud explores the significance of listing Mordechai’s lineage in Esther 2:5, “There was a Jewish man [lit., a man from Judah] in Shushan the capital, whose name was Mordechai, son of Yair, son of Shimi, son of Kish, a Benjaminite [ish Yemini]”. The Talmud asks, why note only these three names? If Mordechai’s lineage is so important, why not trace it all the way back to Binyamim? Perhaps, the Talmud suggests, this is not a lineage of birth so much as a lineage of character. Ben Yair suggests that he was “a son who (Yair) brightened the eyes of the Jews through his prayers”. Likewise, Ben Shimi suggests he was “a son whose prayers were ‘heeded’”. Perhaps. But then the Talmud notes another apparent contradiction in the verse. Mordechai is referred to as Yehudi (from the tribe of Judah). He is also referred to as Yemini (from the tribe of Benjamin). He can be one or the other, but not both!

Rav Nachman suggests that Mordechai’s father was from the tribe of Benjamin and his mother from the tribe of Judah. As such, he would correctly be crowned by both tribes, with the families of each vying with one another for the honor and prestige of Mordechai’s birth.

My grandfather studied these contortions to find merit in this odd family tree but then dismissed them as unnecessary. We had only to listen carefully to what Rava says regarding this discussion to grasp the deeper truth. Rava, my grandfather notes, follows his own shita. He declares that the knesses yisrael – the community of Israel – said the opposite [from this explanation]. Rather than shower Mordechai with the accolades described in the Talmudic passage, they assigned blame, not credit to Judah and Benjamin. In their eyes, Mordecai was not a hero but the source of their trouble. They said, Reu mah asah li Yehudi u’ma shileim li Yemini – Look what the one from Judah did to me and what the one from Benjamin paid me!

And what had the one from Judah done “to me”? He, King David, from the tribe of Judah, did not kill Shimi. And from Shimi descended Mordechai, who provoked Haman by not bowing down to him (even if one were to argue that Mordechai could not bow to Haman who made himself an object of worship, nevertheless the Jews of that generation blamed Mordechai for all their troubles). And what had the one from Benjamin paid “me”? Saul, from the tribe of Benjamin, did not kill Agag [God had commanded Saul to eradicate the nation of Amalek. Saul however, spared Agag, the king of Amalek] and to what end? Haman, descended from Agag, oppressed the Jews and sought to destroy them.

By a failure to act, members of Mordecai’s family tree brought about the suffering of the people. This observation is polemically opposed to the opinions that hold that ish Yehudi haya b’Shushan ha’bira is laudatory!

Rava is saying that both miss the point. It is not one or the other. It is neither one or the other.

My grandfather draws attention to Rashi’s comment on the first words of Rava’s approach, Rava amar kneses yisrael amra l’idach gisa – the community of Israel said the opposite. Rashi says, “This is derogatory (l’tzeaka) and not complimentary, Ish Yehudi (the one from Judah) and Ish Yemini (the one from Benjamin) they were the cause of all this tzaa’r suffering!”

My grandfather notes that in this comment and the one declaring that, “one is obliged to become intoxicated…” Rava is being consistent! In making this observation, my grandfather brilliantly makes clear that the adage that “Not all that meets the eye is the truth”, is true!

* * *

In an article published on Aish.com and taken from his book, “The Shul Without A Clock” – Second Thoughts from a Rabbi’s Notebook, Rabbi Emanuel Feldman notes that Purim is the holiday in hiding. The idea of concealment is woven in the name of its heroine, Esther (Hebrew root: s,t,r – hidden) and her strangeness in the eyes of the king, ein Esther magedet moledetah, Esther did not reveal her origins… (Megillah 2:20).

Esther and Mordecai, who trace their beginnings to Rachel, share her ability to conceal her true, deep feelings. Certainly, Rachel’s son, Joseph, understood the power of concealment – and revelation – when appropriate. Indeed, in the story of Purim even God is concealed!

And yet, we see in Purim a mirror image to our most solemn observance, Yom Kippur. Rabbi Feldman writes, “The lesson is clear: God can be served not only in the solemnity of a Yom Kippur, but also in the revelry of a Purim. God is present not only in the open ark of Yom Kippur when spirituality seems so close, but also in the open food and drink of Purim when spirituality seems so remote. It is much more of a challenge to remember God amidst the revelry than to remember Him in the midst of the solemnity.”

* * *

Often, we arrive at conclusions before we know the entire story; before we do our due diligence to context, history, and perspective. We jump to conclusions based on personal prejudices and leanings.

From our perspective, the story of Purim turned out well. So, we reflexively accord Mordechai accolades. He is ben yair – brightness. He is ben shimi – his prayers were heeded. He is ben kish – he knocked [on gates of mercy]. But wait! Rava cries out, “aren’t you ignoring what really happened? Aren’t you intoxicated with your own brand of ‘wine’ (prejudice, mindset) and failing to differentiate between who is really cursed and who is really blessed?”

He is asking us; Shouldn’t you dig deeper into what really happened? Shouldn’t you question how these events came about and, most importantly, how could these atrocities have been avoided?

Rava is challenging us to dig deeper into the texts to discover Mordechai’s lineage and how that lineage plays out in our Purim drama.

My grandfather draws our attention to our need to be completely honest in understanding our own personal anguish and struggles, as well as collective and national suffering. It’s so easy, and seductive, to lay all the blame on the villain – whoever you believe the villain to be!

But, a candid look into the facts creates a different view and perspective.

Rava is claiming that the two main Purim personalities are to a certain extent being confused! Rava declares, knesses yisrael amra l’idach gisa – “the community of Israel said the opposite”! They did not give Mordechai a testimonial dinner with bright lights and plaques, but idach gisa. Says Rashi, li’tzeaka ve’lo li’shvach – the community of Israel viewed Ish Yehudi and Ish Yemini as causes of distress, agony – not sh’vach. Rava demands, Let’s call a spade a spade!

Which is not to misunderstand who Mordechai is in the Purim narrative. He was a righteous, courageous tzadik and Haman was a wicked glutton and anti-Semite. Certainly, there is no moral parity between them. But – and this is a big ‘but’ – from the perspective of one’s suffering and agony, one can easily confuse right and wrong. For suffering and agony are also a kind of intoxication. After all, who would ever imagine that great heroes, King David or King Saul would stand as root causes of crises and tragedies to generations later?

Inherent in my grandfather’s novel approach is also the idea that when one is confronted with personal or national tzaros and “it all works out” in the end, there is a neis – a miracle, that is certainly wonderful and reassuring. So, laud and praise Him for all the miracles.

But wait! Rava insists. You may very well be so intoxicated (i.e. you have such preconceived notions) that you can’t differentiate between the arur and the baruch, between Haman and Mordechai. Do not be confused. Do not let the neis of the dawning day blur your reasoning and understanding. It was not all sweet like honey. It was li’tzeaka as Rashi says. Distressing. Hurtful.

If only, even while suffering and in pain, some could fully and honestly evaluate the situation with integrity, perhaps then God’s intervention would not have been needed at all! Remember, God does not want us to need miracles. Like any loving father, He wants His children to be able to successfully solve their difficulties with honesty and integrity.

So much of our personal and collective experiences are defined by our inability to view life’s realities candidly and clearly, as Rava would have us do. As a result, we are stuck in our suffering, thinking “this is really what is happening”. But is it? Is this what is happening or is it our confused, intoxicated imagination that make it seems so?

Rava would demand we find the way to distinguish so that we could be sure.

In my grandfather’s own words: