Posted on 05/05/22

It would require 97 years of storytelling, possibly even longer, to fully and accurately capture the life of my Rebbe, Hagaon HaRav Nota Greenblatt, ZTZ”L. Rav Nota, as he was known, passed away last Friday, erev parshas Achrei Mos. He was almost 97 years old.

I say it would take at least 97 years to recount his life story, because every moment of his 97 years of life was a story; every moment was a lesson. He was a man who utilized every second to its fullest extent. His life was greater than any mussar schmooze. Rav Nota accomplished more during his time on this world than many people would be able to accomplish in multiple lifetimes; and I am only referring to the parts of his life that we actually know about. The true extent of his greatness is known only to the Borei Olam.

I merited to be one of Rav Nota’s first talmidim, and also a part of Rav Nota’s final tranche of students. What do I mean? Rav Nota was not your typical gadol. He was not a maggid shiur or a Rosh Yeshiva. He was not even the Rav of a shul. Yet, over the course of his 70 year career as a Rabbi, he mentored and learned with hundreds, if not thousands, of rabbonim, yungerleit, educators, and individuals who consider him their Rebbe. However, during the years 2014-2015, a small group of bachurim travelled to Memphis to learn with Rav Nota.

At the age of 90 he started learning with this small kibbutz of bachurim, which he called the Yeshiva Gedola of Memphis. This was the first time he taught Torah with the goal of imparting his derech halimud to talmidim in the context of, what one would refer to colloquially as, a Rebbe-talmid relationship. Only 10 or 11 bachurim went through the doors of the yeshiva during its 1 year of existence. I was among them.

The year I spent learning with Rav Nota, or The Rav as we referred to him, was the greatest year of my life. During the course of the year, Rav Nota molded my entire vision of what a meaningful life is, my values of what is important and what is not important, my aspirations, and my derech halimud. To me, he was the epitome of a Gadol b’Yisrael.

Rav Nota was among the last of the European Gedolim to walk this Earth. This is even more surprising given the fact that he never learned in the yeshivos of Europe. He was born in the United States and his formative yeshiva years were spent in the United States and Eretz Yisrael, never in Europe. However, as his son Rav Yakov Greenblatt Shlit”a, explained in his hesped for his father, Rav Nota was a product of European Rebbeim of 100 years ago; Rav Dovid Leibowitz, Rav Yasher Ber Soloveitchik, Rav Michel Feinstein, and finally the Rabban shel Yisrael, Rav Moshe Feinstein. He absorbed their Torah, observed their every movement, and formed everlasting bonds with them. As a result, wherever Rav Nota would walk during his lifetime, they would walk with him. They became a part and parcel of him.

Rav Nota told us many times that his greatest trait was that he never let a gadol get away. If he had a chance to meet a great Torah scholar, he seized the opportunity. As a result, he formed close bonds with many of the most notable Torah personalities of the 1940’s and 1950’s, including the Brisker Rav, Rav Aharon Cohen, Rav Yaakov Safsal, and many others. These interactions shaped him into the Torah giant that he would become. The Rav would often regale us with stories of these personalities and others. When he retold a story, it was as if he was reliving the moment; he put all of his kochos into it. If the story was sad, he cried, if the story was funny he laughed, and if the story was maddening, he became inflamed. “My stories are Toras Emes,” he would often say, “I witnessed these stories with my own eyes.” They were a part and parcel of who he was. In fact, he would often connect his stories to divrei Chazal, or a shakla v’tarya in the Gemara.

And yet, in almost direct contradiction to his roots, Rav Nota was the quintessential American Rav, with an intimate understanding of the needs of and problems facing modern-day American Jewry.

After all, he was the “Rav of the South”. His heart was rooted in the study halls of the great European Yeshivos of Brisk and Slobodka, yet his body and mind were rooted in the United States where he toiled endlessly to build and strengthen the Orthodox Jewish community, particularly in the South.

He knew how to interact with his constituents. He was very sharp, and he would often employ humor and wit in his dealings with people. I remember that someone once asked him whether the haftarah of Shabbos Chazon should be read to the tune of Eicha, or whether such a minhag was incorrect due to it being a public display of mourning on Shabbos. He answered laughingly, “It is better to end up in gehinom with the rest of klal yisrael than to be alone in Gan Eden.” We once ate a Shabbos seuda with Rav Nota. After the seuda, he went over to his Rebbetzin, yblch”t, to thank her for the meal. “Rebbetzin, a shiur I say better, but a meal you make better.” The Rebbetzin, who is quite quick-witted herself, responded in her southern accent, “Oh Rabbi! Flattery will get you everywhere!”

Rav Nota was a naturally compassionate, patient, empathetic and easy going person.

I was once sitting next to him in shul, and a boy who had lost his hair due to oso machala was sitting in front of him. Rav Nota was visibly moved, and there were tears in his eyes during that shemona esrei. Another time, there were two little boys who were trying to get a dollar into the slot at the top of the pushke, but it was too full and they could not get it in. The Rav watched them amusedly, and after a little while he walked over to the bima and opened the top of the pushke so they could stick the dollar in.

Despite his natural kind-heartedness, he was not a pushover. When required, which could be quite often, he was firm, unwavering, and even stern. When it came to kavod HaTorah or matters of Jewish identity there was no such thing as compromise or patience.

When Rav Nota was a young man he was once standing in line at the post office and a man started talking to him about Shabbos. The man asked him skeptically how flipping a light switch on Shabbos could be prohibited; all you are doing is flipping a switch?! At the time, the electric chair at Sing Sing prison was running around the clock. Rav Nota asked the man, “What about the man who flips the switch to the electric chair? He is just flipping a switch right?” The man didn’t know how to respond. Rav Nota concluded “What matters is not the action, but what you accomplish through the action.”

Rav Nota told us that his mother would tell him to dream big, and that is exactly what he did. At the age of 24, Rav Nota moved to Memphis, a place devoid of Torah, and turned it into a thriving Jewish community. Rav Tzvi Rosen of the Star K pointed out to me that this was at a time when there were only around forty bachurim learning in the Lakwood Yeshiva, and even in the Tri State area, Orthodox Judaism was unpopular. In the South, many shuls were transitioning from Orthodoxy to Conservative Judaism. Within his first year in Memphis, Rav Nota, still a bachur, together with Rav Yehoshua Kutner Ztz”l, started the Margolin Hebrew Academy. Rav Nachum Lansky Shlit”a of Yeshivas Ner Yisrael was a member of the academy’s first class. Many families are now shomrei Torah uMitzvos due to Rav Nota’s mesiras nefesh.

Before long, Rav Nota became the go-to address for all matters of Jewish life in Memphis and greater Southern United States. He was a world-renowned expert in eiruvin, mikvaos, kashrus, and all other matters of Jewish law, and he was the United States’ premier expert in gittin and chalitzos. Rabbonim from all over America would seek guidance from him.

Rav Nota was tremendously selfless. If someone needed his help, there was no distance too far and no obstacle or expense too great that would prevent him from helping his fellow Jew. The stories of his self sacrifice on behalf of agunos and other people in need are almost endless. For decades, as has been retold many times, he would leave home Sunday morning and not return home until Thursday evening. During that time, he would travel all over America, involved in matters of the klal. When I learned in Memphis, the Rav, who had just turned 90 years old, began to limit the amount of time he was away from home, but only because he felt a responsibility to be present for his talmidim. During that time, he would only travel a few times a month!

Rav Nota took a particular interest in mentoring rabbonim and yungerleit who lived in smaller “out-of town” communities. This, he felt, was the next great frontier, and the place where klal yisrael’s efforts should be expended. He would often encourage bnei Torah to move out of town. “They don’t need you in Baltimore,” he told me.

Despite his gadlus in every area of halacha, Rav Nota was first and foremost a lamdan. He was a man who lived for the klal, but his fuel was the Torah. It occupied his mind constantly. He was a product of the great Brisker Roshei Yeshiva, and kodshim was his bread and butter. However, he had other interests as well. One only needs to look in his sefer, K’Reiach Sadeh, to see his mastery of all areas of Torah, including Targum Onkelos and dikduk.

The Rav was not well known among the Orthodox Jewish populace. Even after 97 years of toiling on behalf of klal Yisrael, most newspapers dedicated only a few pages for covering the news of his death. During his lifetime he kept himself hidden. Those who needed to recognize his gadlus did, and he felt no need to publicize his greatness to those who did not need to know. A frum man from the Tri State area was once passing through Memphis and he sat next to Rav Nota for Mincha. I was sitting nearby and was able to hear the conversation. Rav Nota asked the man who he was and what he was doing in Memphis. The man said his name and that he was passing though. He then asked Rav Nota, not knowing who he was, “and who are you?” Rav Nota responded, “Me? My name is Greenblatt.” He turned to me and gave me an amused smile.

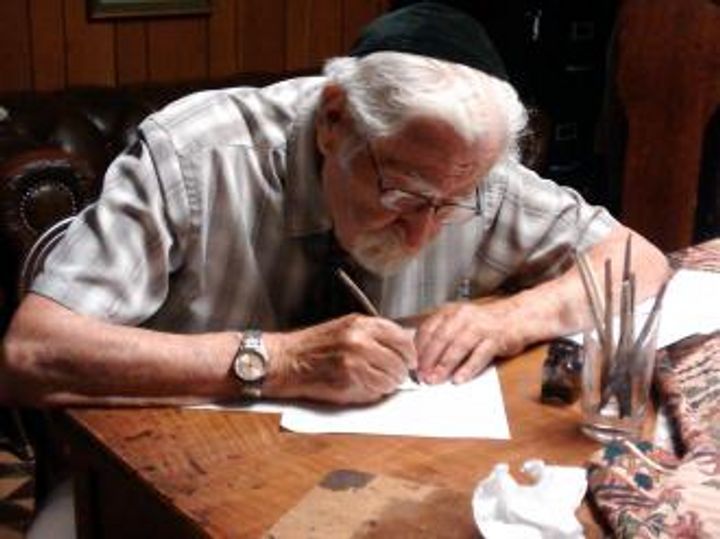

The Rav shied away from unnecessary honor. The only thing he demanded was that he be treated with the same common decency that one would treat any person, but he did not demand any special kavod. “Pashtus is Gaonus, simplicity is genius,” was a mantra that he lived by. He dressed simply, he acted simply, and he lived simply. In fact, the Rav wrote his sefer K’Reiach Sadeh as simply as possible without any added fluff or additional explanation. He included only what was necessary for a reader to understand his words and nothing more.

A memory that is embedded in my mind is something that took place every Shabbos afternoon. Rav Nota had a chavrusa shaft with a local baal habos. Contrary to what one might think, they did not learn Gemara, halacha or machshava together. Rather, they learned Chumash with Rashi. The baal habos would read through a pasuk with Rashi’s commentary in Hebrew, and Rav Nota would sit patiently and translate the words line after line. It was not beneath the honor of this great Torah scholar to sit for an hour every week and translate Chumash and Rashi for someone who sincerely wanted to learn but lacked a formal Jewish education. To me, this showed Rav Nota’s true greatness. He was a Torah giant, yet at the same time he was a man of the people.

Another story that illustrates the Rav’s humility is a story that Rav Nota recounted to us about a meshulach who once came to visit him. Rav Nota was an avid collector of rare seforim. Rav Nota suspected that this meshulach waa stealing seforim, so he distracted the meshulach and while he was not looking, he retrieved the stolen seforim from the man’s bag. He never confronted the man about it, and when their meeting was over he wrote the man a check and sent him off. Rav Nota explained that desperation can often lead people to do things that are wrong, and he himself understood the taiva that someone might have for rare seforim. He did not feel he was in the position to chastise the man about it.

Although I had the privilege of observing Rav Nota in his various roles within the community, the role that I observed him in most intimately was that of a Rebbe to his Talmid. I am not referring to his mastery of Torah, or his ability to explain the most intricate of Torah concepts to anyone, even someone without a yeshiva background. Rather, I am referring to the care and concern that he showed to every one of us. If a bachur was sick and missed shiur, the Rav would show up at the dormitory with a big container of chicken soup. He was full of praise for his talmidim, and he rarely gave mussar. He made sure to find the maalos that each of his student excelled at and praise them frequently. “This bachur is an ilui, this bachur knows every peirush, this bachur is a baal svarah yeshara, this bachur is a mensch” and so on. He also allowed us freedom to follow our own path. When I asked him for permission to leave for a Shabbos to attend a Shabbaton for Yeshivas Ohr Yisrael of Atlanta he responded, “my yeshiva is like the yeshiva in Volozhin. The bachurim are gedolim! They can come and leave as they see fit.” Later, when his talmidim would return to visit the Rav after that year in Memphis, he would greet them with a big Shalom Aleichem and a kiss on the cheek that was wetter than the Mississippi river. Despite his still busy schedule, he would sit down with them for hours to catch up, schmooze, and talk in learning.

To those who knew Rav Nota, he was larger than life, he was invincible, and, to our great sorrow, he was irreplaceable. His passing is a tremendous loss for his family, for his talmidim, for the community of Memphis, and for Klal Yisrael.

Yehi Zichro Baruch, and may he be a meilitz yosher for his Rebbetzin and all of Klal Yisrael.