Jerusalem, Israel - Oct. 17, 2018 - Yad Ben Yizhak Zvi, located in the Rechavia neighborhood of Jerusalem, Israel, hosted a conference of the Israeli Society for History and Law, on October 8, 2018.

The full day program of academic presentations involving law and history, included one session on Law in Halakha, moderated by Rabbi Levi Cooper.

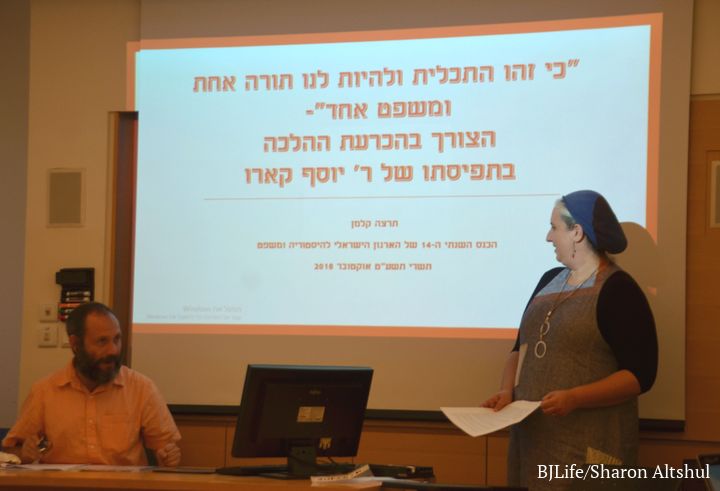

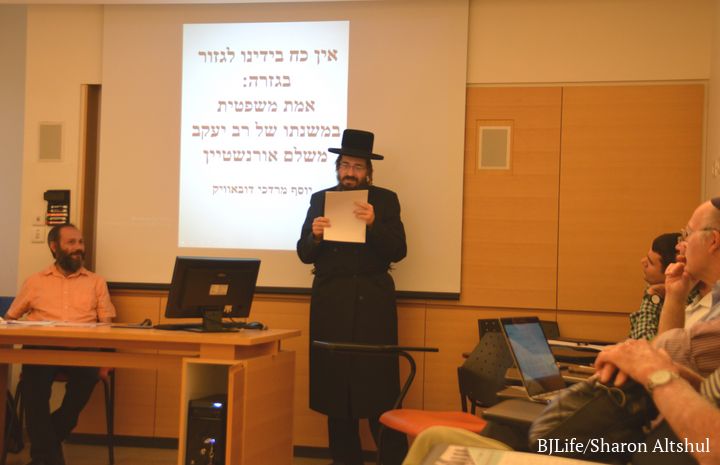

Tirzah Kalman, Eliezar Goldstein, Yosef Mordechai Douveck and Moshe Schorr used slide presentations to illustrate aspects of halakha discovered in their research.

Schorr, a computer science student at the Technion, based his talk on a project initiated and developed with Baltimore native Rabbi Elli Fischer. Their project, called “HaMapah”, analyzes rabbinic responsa, “She’eilot U-teshuvot” with the aid of computers.

The goal of their project is to develop methods for understanding the nature of rabbinic authority. Responsa are created when one rabbi, usually a local rav, asks a rabbi of greater stature, a posek, for a ruling on a halakhic issue. There is always a choice of whom to ask a question. What influences the decision to consult this particular posek? And the corollary: What can a posek do to persuade his audience he is a trustworthy arbiter? In other words, how is rabbinic authority accumulated.

Thus far, their research has focused on creating maps of “spheres of influence.” Many responsa include information about their addressees, and certain poskim were in fact very meticulous about recording this information, while others were equally meticulous about excluding it. By plotting information about addressees on a map, Schorr and Fischer have obtained a detailed representation of the spheres of influence of various poskim.

One example Schorr used was a map that compares the sphere of authority of the Chatam Sofer and of Rabbi Akiva Eger. The two poskim were contemporaries and had family ties - Rabbi Eger was the father of the Chatam Sofer’s second wife. As the map shows, each was a major posek; between them, they wrote over a thousand responsa to about 300 different localities. However, the map also showed they operated in almost completely distinct geographic realms: Rabbi Eger received questions primarily from Prussia, and Chatam Sofer almost exclusively from within the Austrian Empire, and primarily Hungary.

Although we are used to thinking of great poskim answering questions “from all across the world” the reality is that the reputations of poskim take time to develop and are constrained by any number of factors.

Another example used to illustrate this was a comparison of Rabbi Yaakov Ettlinger, author of Binyan Tziyon, with Rabbi Shalom Mordechai Schwadron, or Maharsham. On one hand, a map of addressees in Binyan Tziyon showed the geographical spread to be fairly wide, though clustered in certain areas. Maharsham, on the other hand, seemed far more concentrated in Galicia and neighboring provinces.

A look at the dates of Rabbi Ettlinger’s responsa shows that he wrote most of them during a twelve year period, which coincided with his editorship of the rabbinic journal Shomer Tziyon Ha-ne’eman. In fact, most of the responsa were first published in that journal, in response to general halakhic queries and discussions among its readers. His geographical sphere of influence corresponded to the readership of his journal.

Maharsham, on the other hand, wrote responsa to 438 different locales. His geographical influence barely extended to Lithuania, Hungary, or Germany, let alone to non-Ashkenazim. However, within the regions of the former Kingdom of Poland, which in his time still had the world’s largest Jewish population, his level of authority was unmatched.

Follow research by Schorr and Fischer, as it develops at www.hamapah.org.

Please note: Moshe Schorr is a grandson of the author